English, German and French second-hand books on golf and its continental kindred games colf, crosse and mail. Click here!

***************************************************************************************

All roads lead to Scotland

At the EAGHC* 10th annual meeting at Valescure, Saint-Raphaël, France, on October 1st & 2nd, 2015, Geert and I gave a presentation called ‘ All roads lead to Scotland’. If you look at this presentation, you know the raison d’être of our book 'CHOULE The Non-Royal but most Ancient Game of Crosse' and our trilogy 'Games for Kings & Commoners'!

Click here to follow our presentation page by page.

And when you have finished, come back here and look at the contents of these books.

* European Association of Golf Historians and Collectors

|

|

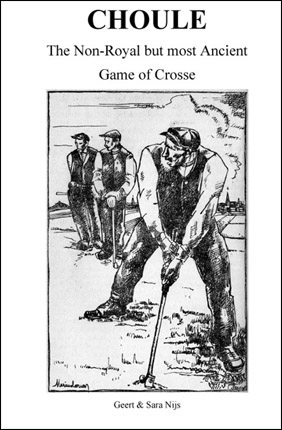

| CHOULE The Non-Royal but most Ancient Game of Crosse 2021 Revised/Extended/Re-designed edition Editions Choulla et Clava |

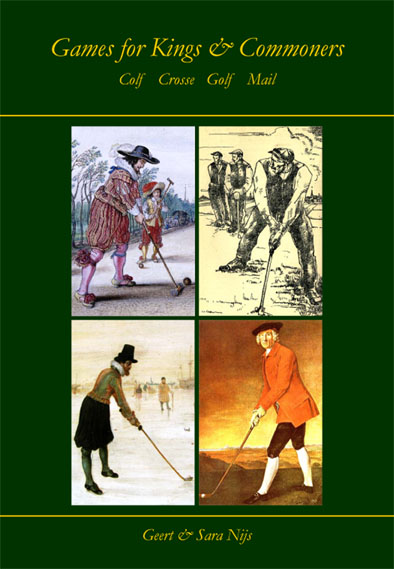

Games for Kings & Commoners PART THREE Editions Choulla et Clava |

|

|

| Games for Kings & Commoners PART TWO 2014 Editions Choulla et Clava |

Jeu de crosse - Crossage A travers les âges (Edition française de CHOULE) 2012 Editions Choulla et Clava |

|

|

| Games for Kings & Commoners 2011 Editions Choulla et Clava |

CHOULE - The Non-Royal but most Ancient Game of Crosse 2008 OUT OF PRINT - SEE 'CHOULE' - EDITION 2021 |

Games for Kings & Commoners PART THREE

The book

| Ordering |

| Reactions & Reviews |

Summary of the chapters of the book

All

over the world, stick and ball games were and are played, which

resemble golf. Several of these games are seen as precursors or even

as the original golf game.

When

making deals in Scotland, did the North Netherlandish and French

merchants swap the wool against their stick and ball games?

Cleeks, kliks and tally sticks

In

a Netherlandish poem from 1656, the name ‘Schotse klik’ is used. Was

such a ‘cleek’ imported from Scotland, or was such a klik an original

Netherlandish club?

A beautiful ice scene painting in which two colvers

are playing towards a hole in the ice.

Nature, measure of all

things

What role did nature play in golf and the continental

golf-like games?

Boxwood for a very hard ball.

Clubs for hitting far and sure

Through the centuries, players have always looked

for ways and means to strike the ball further and straighter.

Gable stone from 1610 at the front of a colf club maker's house.

The little Ice Age in the Low Countries

How come that during the Little Ice Age, Netherlandish

colvers moved by the thousands to the frozen canals, rivers and lakes to play

their game of colf?

The Little Ice Age in Scotland

During the Little Ice Age in Scotland, people enjoyed skating and curling on the frozen lochs and firths. Where were

the golfers? Didn’t they play golf on the ice?

When

the firths and the lochs were frozen, many Scots loved to go out on the

ice to enjoy skating, curling, walking, and taking some refreshments.

In the last

decades, archaeologists excavated several Netherlandish ships from the

16th and 17th centuries, wrecked near the Shetlands and

in the ‘Zuyderzee’. In the remains of the shipwrecks, they found colf clubs and

club heads.

One of the excavated brass slofs (17th century) seen from

different angles: the strike face, the top and the back of the head.

Haarlem: 600 years of colf - kolf - golf

An

ancient city with more than 600 years of colf, kolf and golf history.

Haarlem had the first ‘official’ colf course (1390) and ‘links’ course

of the Netherlands (1913).

Early 17th-century ice scene under the walls of Haarlem.

Watched by partners, opponents and other spectators, a colver aims at an

invisible target, perhaps the inner side of the boat.

Criminality in the world of colf history

Many golf collectors love to have a specimen of the

continental golf-like games in their golf collection. Be careful when being

offered a ‘bargain’ you cannot refuse.

Is the long game in golf a unique feature that sets the game apart from all other golf-like games?

Colf has always been a field game. When playing on

frozen fields was not possible, colvers went onto the frozen ponds, canals,

lakes and rivers to play an adapted short game.

Throughout history, the names of golf and the continental games were written in different ways. What is the origin of the names?

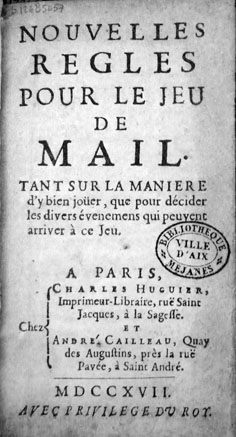

The first visible reference to the game of mail or

better pallamaglio in Naples.

What happens with a ball without dimples? Could we do

better with ridges or grooves instead of shallow cavities?

Dimples make the difference. The player can hit a dimpled ball more than twice as far as a smooth ball.

The publication (format 18 x 26 cm) contains 276 pages with over 200 pictures in full colour and black-and-white.

The price of the book is EURO 15 plus p & p.

Payment: via PayPal or an international bank transfer (EURO-accounts only).

Because of the restricted number of copies printed, the book is not available from the bookshop but can be obtained directly via

Ed Durfey, United States of America

I wanted to drop you a note and tell you

how much I enjoyed reading your books. The amount of documented research was

impressive- and in my (novice) opinion, you gave a balanced view of

the history of golf, and ball and stick games. Thank you.

February 2022

Johann de Boer, club referee and

member of the European Association of Golf Historians and Collectors, The Netherlands

For more than a hundred and fifty years of golf history publications, we had to do with some superficial information on these games in the margins of the many golf books. In the trilogy ‘Games for Kings & Commoners’, the authors have been able to explain in depth what kind of games the ‘continentals’ played and how they compare with each other. Regularly, golf is used as a benchmark. The authors must have spent numerous hours in archives, museums, libraries, etc., in the different countries to retrieve information which regularly surpasses the knowledge on specific aspects of golf history.

The ‘Tee-off’ chapter ‘All Roads lead to Scotland’ tells us about the many golf-like games which seem to have travelled from all over the world to show the Scots how to make fun out of hitting a ball with a crooked stick and how improbable these assumptions are. The use of the word ‘Schotse klik’ (Scottish cleek) in a Netherlandish poem from 1656 could arouse discussions about the mutual influences between golf and colf. Did the Scots export golf clubs to the Netherlands as the Netherlanders have exported colf balls to Scotland in the 16th century?

It is interesting to see the development of the crooked sticks in the games from the early beginnings. It is rather surprising that so much is known about the ancient colf and crosse clubs while so little is known about the ancient Scottish clubs other than ‘rough clubs’ and ‘sophisticated clubs’.

It has always surprised us that so many 16th and 17th-century’ pictures of colvers exist while the first ‘golf painting’ dates from the mid-18th century. The explanation of this phenomenon is a real eye-opener. When you have read the above explanation, you probably wonder where the Scottish golfers were during the ‘Little Ice Age’ in the 17th century. Several pictures are shown with skaters and curling players on the frozen lochs and firths, but no golfers can be distinguished.

Colf club heads can still be found in the fields and in the towns of the Netherlands. However, some time ago, nautical archaeologists discovered colf clubs and heads from the 17th century in shipwrecks near the Shetlands.

It is amazing what prices some of these club heads made at auctions. When such stunning prices were made for club heads, many collectors would be eager to obtain such an artefact, especially when it is offered at an absolute ‘bargain’ price.

The chapter on criminality in the city of Haarlem is a warning that you should prepare yourself before responding to such offers. The history of the town of Haarlem is closely linked to colf-kolf and golf. From the first ever official colf course from 1389 to the first Netherlandish ‘links’ golf course from 1915, the town’s history is interwoven with the games.

The authors assume that the four games all started as street games and eventually changed into a long game in the open fields. Did the players go voluntarily or were they forced by the councils?

So far, many words have been spent on the ‘names for the games’; Geert and Sara Nijs make a rather simple and clear contribution to these discussions.

These and several other aspects of the four games are dealt with in 276 pages of Part Three, interlarded with hundreds of pictures, maps and documents in full colour and black & white. The publication is the final continuation of the trilogy ‘Games for Kings & Commoners’. The three books can be read independently.

July 2015

John Hanna, Past Captain of

the British Golf Collector’s Society and Past President, today Vice-President, of the European Association of Golf

Historians & Collectors, Great Britain

If there are any researchers who have spent as much

time as Geert and Sara have done in investigating the history and the playing

of stick and ball games throughout Europe and beyond there cannot be many!

This is evident by the amount of material in their latest book. Its 276 pages

are filled with an enormous amount of most interesting material. Also, it is

enhanced by around 200 maps and coloured photographs many of which have been

taken by Geert. The book opens with a brief description of the varied stick and

ball games found in Europe and beyond. All the more common games are included

such as Colf, Crosse, Mail and, of course, Golf. However, our researchers have

gone further and report on games from Russia and China. Some other references

have made in respect of golf in China and the pictures used a game very similar

to golf. It dates as far back as the mid-15th century around the

same time as golf was first played. An interesting question the authors pose in

relation to the founding of golf – when they state ‘Could it be that golf is

just an independent Scottish game, invented by the Scots, developed by the

Scots and spread over the world by Scots’.

Book review in 'Through The Green', magazine of the BGCS, September 2015

Games for Kings & Commoners PART TWO

This

new publication, a continuation of ‘Games for Kings and Commoners’

(2011), counts ten chapters on 280 pages, including more than 200

pictures, both in full colour and black and white. The authors deal

with several new historical aspects of the related games of colf

(kolf), crosse (choule), golf and mail (pall mall). They discuss,

explain and compare the games to develop a better insight into how and

by whom, with what equipment and under what rules they were probably played in the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance.

| Ordering |

| Reactions & Reviews |

Summary of the chapters of the book

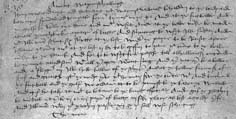

Original text of the Act of the Scottish Parliament, banning golf and football (1457).

Detail of a painting from the 18th century showing players on the mail alley in the Schleiβheim Schlossgarten.

Who needed an 'aide' to play the game?

It

is a well-known fact that in golf, wealthy players hired a sort of

assistant. But what about the colf players, the crosseurs and the mail

players? Did they use a kind of caddy to carry clubs, to make tees, to

warn people in the field, to look for lost balls, etc.?

This painting shows a young boy standing near the colf player, probably holding the overcoat when the player in the 'freezing cold' is going to strike the ball, obviously the function of a hired caddy too.

Maliën in the Netherlands

For

hundreds of years, the Netherlanders played colf, both in-town, in the fields

and on the ice. It was mainly a people’s game. At the beginning of the 17th

century, a new game entered from France into the Netherlandish society.

What kind of people played this new game, and where did they play? Did it become

a popular game, and did it last long?

Drawing of the mail court in Leiden alongside the 'Trekvliet' (barge-canal).

I'd like to teach the world to swing

We

all know how difficult it is to hit a ball ‘far and sure’. We need

lessons from a professional and frequent the driving range to practice

before we are even allowed to play on the course. Who taught kings,

aristocrats, bourgeois and commoners 500 years ago how to swing a club?

17th-century

painting, showing a professional or a personal friend, teaching a young lady

how to handle the colf club.

Who is this little man standing between angels, saints, kings and abbots, swinging a small stick at a large ball on a huge stained glass window in Gloucester Cathedral?

The publication (format 18 x 26 cm) contains 280 pages with over 200 pictures in full colour and black-and-white.

The price of the book is EURO 15 plus p & p.

Payment: via PayPal or an international bank transfer (EURO-accounts only).

Because of the restricted number of copies printed, the book is not available from the bookshop but can be obtained directly via

Ed Durfey, United States of America

I wanted to drop you a note and tell you

how much I enjoyed reading your books. The amount of documented research was

impressive- and in my (novice) opinion, you gave a balanced view of

the history of golf, and ball and stick games. Thank you.

February 2022

Albert Bloemendaal, golf historian and member of the European Association of Golf Historians and Collectors, The Netherlands

September 2014

Dick Durran, Honorary Life Member of

the British Golf Collector’s Society, Great Britain

Geert and Sara Nijs have published Part

2 of Games for Kings & Commoners, which review new findings on the games of

Colf, Crosse, Golf, and Mail. Part 1 was published in 2011 to great acclaim and

Part 2 certainly does not disappoint.

They examine a number of

topics and question some long held theories on the origins of golf. For example

the first reference to golf is in the Act of Parliament of Scotland dated 6th

March 1457 when football and golf should be utterly condemned and stopped. As a

previous Act dated 26th May 1424 only forbad football was it

reasonable to assume that the sport of golf started sometime between these

dates? A second view suggested by a history scholar might be is that

perhaps golf at that time was not as we know it today. Perhaps it was a form of

hockey or even shinty. The authors counteracted rather convincingly this argument. One thing that is reasonably certain is that in 1491

when yet again golf again was forbidden this was golf as we know it today. Why?

Because just twelve years later King James IV bought a set of golf clubs.

Other topics are covered.

They chart the spread of golf from

Scotland to other countries as well as the spread of Jeu de Mail, Jeu de

Crosse, and Colf internationally. Colf

for example even reached Sri Lanka and the Cape of Good Hope. Colf was played already in America in 1650. When the Dutch

lost the second Anglo-Dutch War the British took over the Dutch trade

settlements and replaced colf for the Scottish game of golf. They

examine the finding of Colf club heads from shipwrecks, caddies used in the

different sports, early written lessons on how to play the different games, the

findings of Steven van Hengel, the little “golfing”

figure in the Crecy window in Gloucester cathedral, and the earliest Rules of

the various games.

Geert and Sara Nijs take

the view that there is no such thing as the final “one and only” truth. The

book is extremely well illustrated and well designed and can be thoroughly

recommended.

Book review in 'Through The Green', magazine of the BGCS, September 2014

Wayne Aaron, member of the Society of Hickory Players, USA

It is another "Opus Magnus". Thanks for all your research efforts and for

sharing them (within this

wonderful

book) with interested collectors like myself.

I want to congratulate you on a really excellent production of both content and quality of production. Yet again you have provided another important book on the history of the game. Well Done !!

August 2014

Prof. Dr. Dietrich R. Quanz, Germany

Juli 2014

Cees A.M. van Woerden, auteur van 'Kolven "Het plaisir om sig in dezelve te diverteren"', France

Juli 2014

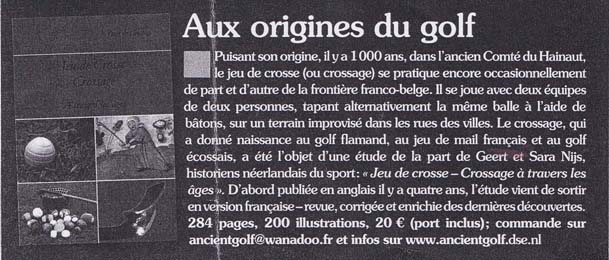

Jeu de crosse - Crossage A travers les âges

Pendant quelques ans, Geert & Sara Nijs, historiens de sport indépendants, ont étudié en profondeur, le passé et le présent du jeu, ses joueurs et l’environnement où il est pratiqué. En 2008, les résultats de ces recherches furent réunis dans un livre intitulé « CHOULE – The Non-Royal but most Ancient Game of Crosse », qui fut reçu avec beaucoup d’intérêt par des historiens de golf et de sports dans le monde entier.

Ce livre esquisse une image du passé et du présent de ce sport, dans son milieu historique, démographique, culturel, économique et religieux. Depuis sa parution il y eut régulièrement des demandes pour une édition française du côté des organisations belges et françaises des sports et du patrimoine.

« Jeu de Crosse – Crossage » n’est pas une simple traduction de la version anglaise mais plutôt une édition complètement revue et corrigée et élargie avec les trouvailles de ces dernières années.

Le livre

| Commander |

| Reactions & Critique |

Résumé du livre

En quoi consiste le jeu de crosse ?

Le jeu est toujours un sport qui se pratique avec deux équipes de deux personnes (comme dans l’original match-play au début du golf). Les équipes jouent avec une seule balle.

Il n’y a pas un combat pour la balle mais l’une des équipes essaie d’éviter que l’autre équipe s’approche de la cible. La balle est frappée à tour de rôle, de façon à éviter une mêlée dangereuse.

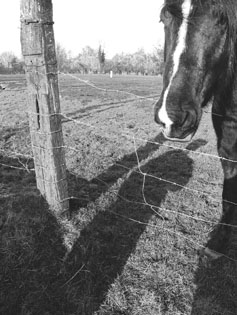

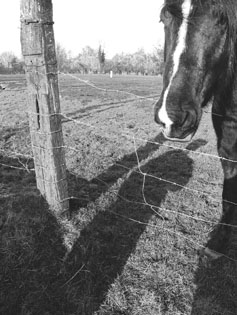

Les crosseurs de la société « Les Amis Réunis » à Gommegnies en France doivent partager leur terrain avec des vaches et des chevaux et doivent jouer les choulettes dans les parties trempées et piétinées du terrain.

On joue toujours avec des balles ellipsoïdes en bois et les

bâtons en bois, pour frapper la balle, ont des têtes ou ferrées ou en

bois. On

pratique toujours ce jeu pendant l’hiver comme le faisaient autrefois

les golfeurs, les colveurs et les joueurs de mail. On joue toujours

dans les rues et sur les places des villes et des villages comme au

golf joué au bas Moyen Age à Aberdeen et Edinburgh et le colf à

Amsterdam et à Bruxelles, ainsi que sur les prairies et les champs

sauvages comme on jouait autrefois sur les links de Leith et Saint

Andrews et sur les champs de Haarlem.

Le jeu de crosse donne une image réelle et historique de la façon dont

on jouait, il y a six à sept siècles, le golf en Ecosse, le colf dans

les Bas Pays et le mail en France.

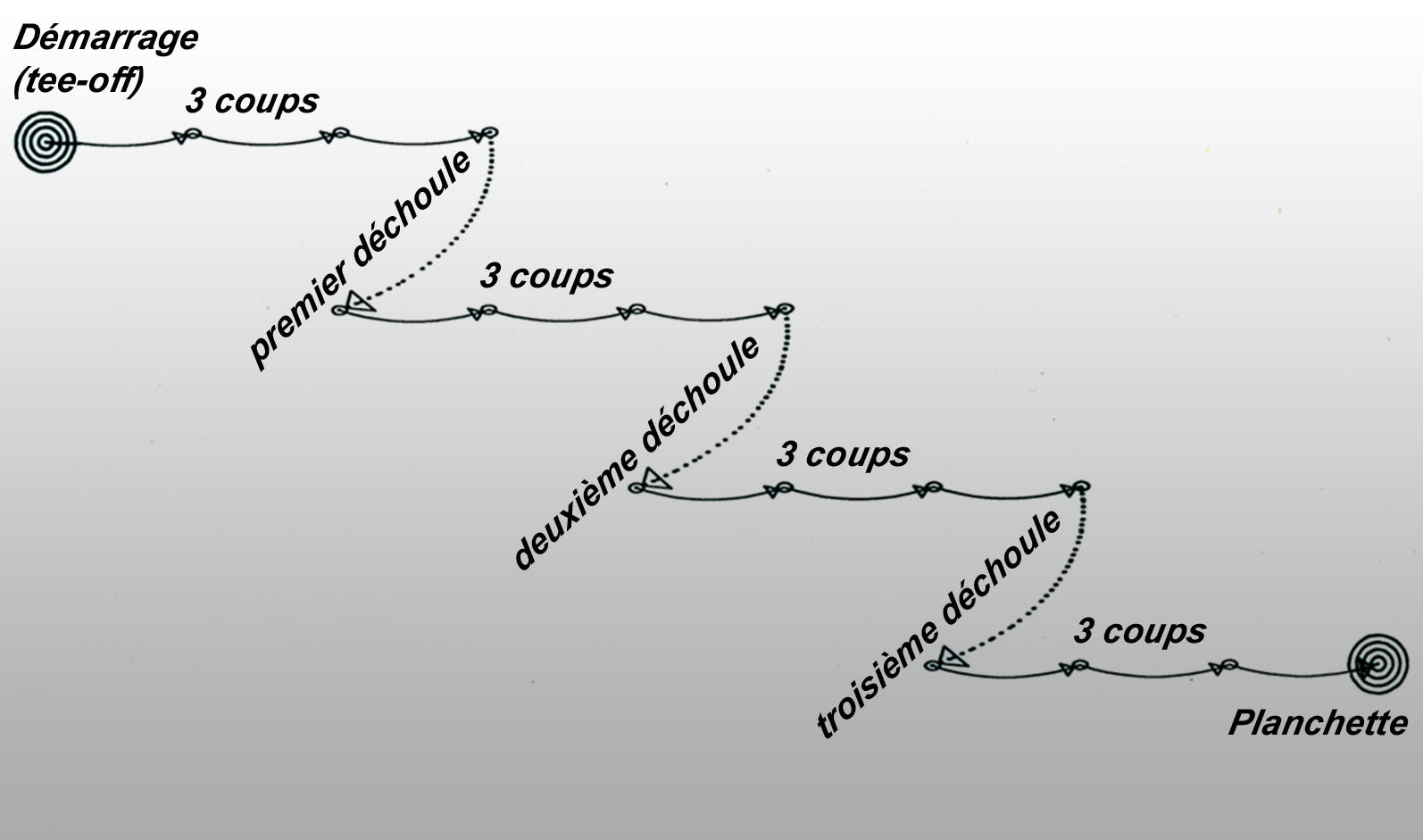

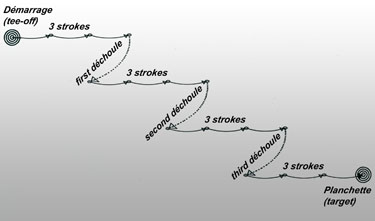

Un match comme tous les dimanches

Le

jeu de crosse est un jeu d’équipe. Il y a une seule balle (la

choulette) en jeu. Une des équipes (les chouleurs) frappe la balle

trois fois affilée et essaie d’atteindre une cible en un certain nombre

de coups. L’autre équipe (les déchouleurs) frappe la balle une seule

fois et essaie d’éviter que les chouleurs s’approchent de la cible.

Les

chouleurs sont les vainqueurs d’une partie (un trou au golf), quand ils

réussissent à toucher la cible en respectant le nombre de coups fixés

au départ, les déchouleurs quand ils réussissent à empêcher les

chouleurs d’atteindre leur objectif. Le match est fini quand une des

deux équipes gagne cinq parties. Un match dure environ 4 à 5 heures.

Au jeu de crosse, il y a trois variantes principales :

Jeu de crosse en plaine

Ce jeu de choule/déchoule, ainsi

qu’il est expliqué ci–dessus, est pratiqué dans les plaines ouvertes de

novembre jusqu’en avril.

Jeu de crosse au but

Ce jeu est un jeu de cible (au golf une sorte de concours de putting). On le joue en été comme en hiver.

Jeu de crosse en rue

Ce jeu de choule/déchoule ne se joue

qu’à mardi gras, à mercredi des Cendres ou aux fêtes des saints, dans

les rues des villes et des villages.

Le

jeu de crosse en plaine est joué des deux côtés de la frontière

franco-belge.Aujourd’hui, le jeu de crosse est joué en Wallonie

Belgique, surtout dans l’ancienne région minière du Borinage, près de

la ville de Mons dans la province du Hainaut. En France, le jeu est pratiqué

dans le département du Nord, plus précisément dans la région d'Avesnois

près de la ville de Maubeuge.

A quelques exceptions près, la

crosse au but est jouée du côté français de la frontière. Le centre

principal est la ville d’Assevent.

La crosse en rue est principalement jouée du côté belge de la frontière à Chièvres et Blaton comme centres très populaires.

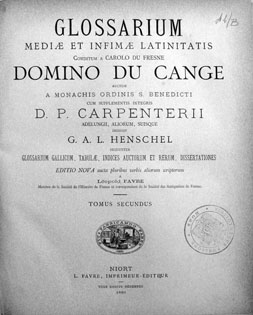

Dans

le dictionnaire, contenant des mots latins populaires du Moyen Age de

la période comprise entre 800 et 1200, on explique le mot

« choulla » comme « une balle frappée avec un

bâton ». Au fil des siècles, le mot choule ou soule, en attendant

un mot français, s’appliqua à une balle, jouée avec les mains et les

pieds. Les jeux dans lesquels on utilisait un bâton étaient nommés «

choule à la crosse ».

Dans le

premier « Dictionnaire de l’Académie Françoise » de 1694,

tous les jeux de balles et de bâtons se disent « jeu de crosse ».

Au 19ème

siècle, on donna des noms spécifiques aux différents jeux de crosse,

comme le football, le cricket, le hockey et le rugby. Le jeu de crosse

n’a pas eu un nom spécifique, et il continue à être appelé « jeu

de crosse ».

Le jeu de crosse en plaine est un jeu d’hiver. La plupart des terrains

de jeu de crosse ne sont pas la propriété de crosseurs mais de fermiers

qui permettent aux crosseurs de jouer sur leurs terrains quand

les vaches sont rentrées dans leurs étables ou quand les champs sont

moissonnés.

Par conséquent, la saison de crosse commence le 1er novembre

(Toussaint) et finit le lundi de Pâques quand la « Grande

Finale » des tournois importants se joue souvent.

Sur la plupart des terrains de crosse, en été, il est impossible de sortir sa balle de l'herbe haute, sans parler des difficultés pour retrouver sa choulette.

Le

jeu de crosse en plaine n’est pas joué sur des terrains bien

entretenus. Le jeu de crosse est joué sur la prairie ou terres à

l’abandon, souvent possédées par des fermiers ou des communes. Il n’y a

pas de tees, pas de « fairways » rasées et pas de

« greens » tondues. Un parcours de jeu de crosse n’a ni

« driving range », ni professionnels, ni boutique de pro.

Les crosseurs doivent partager le terrain avec des vaches et des

chevaux et doivent jouer les choulettes dans les parties trempées et

piétinées du terrain mouillé.

Le club de crosse est constitué d’une tête en fer, d’un manche en frêne et d’une poignée.La tête en métal a deux faces. La face « plate » est droite et est utilisée pour taper loin, quand la balle est dans une bonne position. La face du « pic » ou « bec » est extrêmement concave et est utilisée pour des positions difficiles et pour les coups d’approche. Une crosse combine les propriétés d’un fer long et d’un « pitching wedge » au golf.

Le

jeu de crosse se joue avec une balle elliptique, appelée

« choulette », un diminutif de « choule », l’ancien

nom de la balle. On ne sait pas pourquoi des balles elliptiques sont

utilisées ni depuis quand.

En France, la choulette officielle est faite de charme. La surface a

cinq rainures peu profondes pour améliorer les caractéristiques de vol.

En Belgique, les crosseurs cherchent librement et constamment des

possibilités pour améliorer leur jeu par l’utilisation de différents

matériaux pour les choulettes, comme du nylon extrêmement dur.

La choulette d'origine en bois (à gauche), comparée avec la balle officielle de charme et une balle de golf.

Aujourd’hui le jeu de

crosse est toujours un jeu d'homme. On considère que les parcours dans

les champs glacés et les terrains sauvages sont moins adaptés aux

femmes.

Depuis que le jeu de crosse a été dessiné, peint ou décrit, les femmes n’ont guère été mentionnées ou représentées.

Le livre d’heures valenciennois « les heures de Guillaume

Braque » contient une enluminure d’une femme, frappant vers une

balle sur un tee.

La plus ancienne

illustration d'une femme, jouant à un jeu de balles et de bâtons. -

Avec l'aimable autorisation de Sam Fogg, London

Il n’y a pas de

tenue réglementaire pour les joueurs de crosse. Les crosseurs ne

portent pas de gants en cuir et n’ont pas de chaussures à pointes.

Parce que le jeu se joue en hiver, les crosseurs portent des bottes

imperméables et des pull-overs ou des blousons chauds et un bonnet.

A mardi gras et au mercredi des Cendres, on joue la crosse en rue dans

de nombreux villages du Hainaut et aussi en Avesnois. Dans certains

villages il est l’habituel de se déguiser pendant ces journées.

Le jeu de crosse est un jeu très traditionnel. Un des usages autour de ce sport est d’avoir des repas traditionnels.

Le jeu de crosse était toujours un sport pour la

classe laborieuse. Les dîners copieux de haute cuisine ne faisaient pas

partie de la vie des crosseurs. Les moules étaient la nourriture la moins chère et aussi la nourriture pour la classe laborieuse.

La

manière dont on jouait le jeu de crosse en plaine (un jeu d’équipe) ne

donnait ni un vainqueur unique ni une équipe gagnante. Une équipe

défiait l’autre pour des boissons gratuites ou un repas gratuit pour

les vainqueurs.

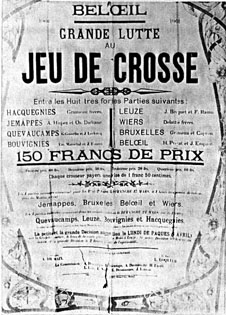

La différence entre de tels

matches et des tournois résidait dans le fait qu’un tournoi demandait

plusieurs journées (week-ends) pour éliminer des joueurs ou des équipes

jusqu’aux petites et grandes finales. On jouait les tournois pendant

l’hiver, et les finales avaient lieu souvent le lundi de Pâques.

Depuis le Moyen Age, on parcourait les pâturages et les rues des villes et des villages. Le jeu dans les champs ne causait pas beaucoup de problèmes, mais à partir du moment où les crosseurs arrivaient en ville dans les rues (et les tavernes), le jeu dégénérait en bagarres et jurons. Les autorités municipales et cléricales étaient régulièrement forcées d’interdire, de limiter ou de modifier le jeu de crosse. En intégrant le jeu de crosse dans le calendrier liturgique, les autorités cléricales essayèrent de contrôler le jeu de crosse.

Un ancien bas-relief de Saint-Antoine.

Pendant

des centaines d’années, Saint-Antoine fut imploré à Havré contre les

maladies contagieuses, comme la gangrène et surtout la peste.

Les pèlerinages à la chapelle

d’Havré avaient lieu habituellement pendant la période hivernale,

surtout les dimanches. Après les cérémonies religieuses, le peuple

allait à la kermesse pour rencontrer les autres, pour boire, pour

manger, pour danser et pour pratiquer des jeux. La porte de la chapelle

de Saint-Antoine était le but final des crosseurs qui faisaient ce

pèlerinage.

Quand au cours du 17ème

siècle, les maladies comme la peste déclinèrent, le désir de participer

au pèlerinage à Havré diminua, mais les crosseurs continuèrent à

célébrer Saint-Antoine, qui était devenu leur patron.

Spécialement le

17 janvier, fête de Saint-Antoine, beaucoup de crosseurs continuaient à

pratiquer leur jeu autour de la chapelle.

Au

moyen âge, on jouait le jeu de crosse en ville : dans les rues et

aux places. Parce que les crosseurs pouvaient facilement blesser le

public et casser les vitres des maisons et des églises avec leur balle

en bois, les conseils municipaux et cléricaux expulsaient le jeu vers

les champs ouverts extra-muros.

Le carnaval est encore la

seule occasion de jouer à la crosse en ville. La petite ville de

Chièvres est un bon exemple de cette tradition du jeu de crosse

carnavalesque.

Dans beaucoup de villes le jeu

était chargé de traditions séculaires comme porter des costumes

carnavalesques spéciaux, manger des repas traditionnels et chanter des

chansons traditionnelles.

Beaucoup

de chercheurs sont d’avis que les guerres ont toujours joué un rôle

important en introduisant des sports et des jeux dans différents pays

et régions.

Une thèse très intéressante

est celle du « voyage » du jeu de crosse de Flandres via la

bataille de Hastings (1066) et de l’Angleterre vers l’Ecosse avec des

chevaliers flamands.

Selon une autre théorie, le

golf écossais pourrait dériver, directement ou par l’Angleterre, des

batailles livrées en France pendant la guerre de Cent Ans.

Au

moyen âge et au début de la Renaissance, la plupart des expressions

artistiques se limitaient aux thèmes religieux. Bien que les sports et

les autres activités de loisir étaient souvent englobés dans la vie

religieuse, il était très exceptionnel que ces activités fassent partie

des représentations religieuses.

Plusieurs auteurs ont étudié

ces illustrations rares afin de découvrir de quelles sortes de jeu de

balles et de bâtons il s’agissait et afin de trouver des corrélations

avec d’autres jeux de balles et de bâtons.

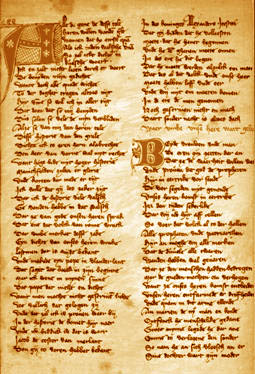

Les jeux de balles et de bâtons, souvent nommés : chôle à la crosse, choule (soule) ou jeu de crosse furent un sujet de la littérature à travers les âges. Plusieurs auteurs n’ont pas donné de précisions sur le type de jeu auquel ils se référaient : Jacob van Maerlant, Jean Froissart, François Villon, François Rabelais, Gilles de Gouberville, Abbé Lebeuf, Charles Deulin, Emile Zola et Achille Delattre.

Expressions, proverbes, chansons et poèmes

Beaucoup

d’expressions et proverbes, utilisés dans la vie quotidienne, ont une

relation avec les sports populaires. Le jeu de crosse est aussi à la

base de beaucoup d’expressions et proverbes, souvent dans le patois

local.

Malheureusement, la plupart ne sont plus utilisées dans la vie quotidienne.

Le jeu de crosse a toujours

été un jeu pour le peuple. Il est évident que beaucoup de chants de

bistrot célèbrent la victoire ou la défaite.

En 2004, « Les Ménetriers » de Chièvres découvrirent un chant traditionnel du crosseur wallon, consacré à Saint Antoine.

En savoir plus sur le jeu de crosse soulève encore beaucoup de questions sur le jeu lui-même, mais aussi sur le grand nombre de similarités et de différences entre le jeu de crosse, le jeu de colf flamand/néerlandais, le jeu de golf écossais et le jeu de mail français. Nous espérons aussi, que nos recherches encourageront des historiens professionnels à prêter une attention académique à l’histoire de ce jeu de crosse et des autres anciens jeux, dont la plupart n’existe plus.

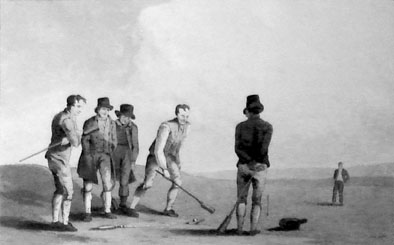

Illustration d'un ancien jeu anglais de balles et de bâtons, toujours pratiqué dans le comté du Yorkshire.

Paiement par PayPal ou un virement international (seulement pour comptes bancaire en euro). A cause du tirage limité, le livre n'est pas en vente au librairie mais directement chez les auteurs par

Réactions & Critique

Rémy Genot, historien local, Bourgogne

Août 2013

Revue de Golf Europeen

Mars 2013

Mes félicitations à vous deux pour l'édition de ce livre d'un grand intérêt pour nous et dont nous ne manquerons pas de faire la publicité.

Décembre 2012

Games for Kings & Commoners

The book

| Ordering |

| Reactions & Reviews |

Summary of the chapters of the book

Clearly unsuitable for women

The fifth column

The hole, the first line of defence

Detail of an illumination in a Flemish manuscript, called the 'Golf Book’, c.1500, in which a colf player is putting the ball into a hole.

Mit ener coluen

The oldest existing document (1267) in which a colf (coluen) was mentioned.

From colf to kolf

The same word, a world of difference. For almost 250 years authors have been confused about the difference if any between the games of colf and kolf. What is the difference between these two games and why did the colvers swap their long game for the peculiar indoor game?

A beautiful early 20th-century tile tableau of an open-air kolf court.

From Pall mall in Great britain

The ‘jeu de mail’ court game as the game was called in

France was very popular with the French kings. It is said that the game called

pall mall in Britain never caught on with Scottish/British royalty other than a

legendary game played once by Mary Queen of Scots. Was British royalty so much

occupied with golf that they did not have the time for playing this foreign

game? Or was it perhaps

the other way around?

pall mall was still played.

Knocking wooden balls around

Crosseurs can hit a choulette as far as golfers could hit a feathery ball.

Swapping woodies for leatheries

If the Scots started their game with wooden balls, why did they swap their 'woodies' for the far more expensive 'hairies' and 'featheries'? Could one hit a leather ball further than a wooden ball or straighter? Was a feathery more vulnerable than a hairy ball? Could one hit a gutty further than a feathery?

The Kings took to the links

According

to most golf history books, Scottish and later British royalty have

played a prominent role in golf, hence the name ‘the Royal and Ancient

game’.

What was that close relationship? Were the royals passionate golf

players, or is the term ‘Royal’ just the result of kings and queens

scattering royal patronage grants around upon humble requests of golf

clubs? Was golf outside Britain a royal game?

Was King Baudouin I from Belgium the best ever royal golf player?

Afterword

The publication (format 18 x 26 cm) contains 260 pages with over 200 pictures in full colour and black-and-white.

The book is published in a limited edition of 250

numbered copies.

The price of the book is EURO 15 plus p & p.

Payment: via PayPal or an international bank transfer (EURO-accounts only).

Because of the restricted number of copies printed, the book is not available from the bookshop but can be obtained directly via

Ed Durfey, United States of America

December 2021

'Tom Morris of St Andrews, The Colossus of Golf, 1821 - 1908' published in 2008; Co-Founder, Past Captain and Honorary Life member of the British Golf Collectors Society, Great Britain

It will undoubtedly be the seminal work for many years to come and I applaud all the research and hard-work, not to mention the time, that you have put into it.

It really is a great addition to the literature of golf and you are to be warmly congratulated.

May 2012

Geert and Sara set out to answer a number of questions relating to the history and development of the various games such as Colf, Crosse, Mail and Golf. The text is slightly repetitive in places but this is unavoidable given the close connections between the various games. The introduction is just that, it introduces the reader to the basics of the three main stick and ball games. The role of women and children is looked at, beginning with the idea that they were unsuitable for these groups, but leading up to date where women now participate in them all, while children are still not taking part in some of them. Clearly this does not apply to golf. It is recognized that the hole is an indisputable feature in golf however the ‘targets’ of the other games are detailed. The early game of colf played as it was over open spaces and on frozen canals clearly had its limitations in a more crowded world, and the authors describe the transition from this outdoor game to the game of kolf which was played in enclosed spaces both indoors and outside. This was the game which was played by the Royals in England when it was called Pall Mall.

A common feature of all of these games is the ‘ball’, and its various forms are dealt with in detail. An interesting chapter deals with how ‘royal’ is the Royal and Ancient game. The involvement of royalty in a number of countries is written about. This is a most informative book.

Book review in Golfika, magazine of the EAGHC, April 2012

David Hamilton, Past Captain of the British Golf Collectors Society, Great Britain

In other aspects of the European games, new images of interest keep turning up and the Nijses have usefully found some more paintings showing holes in the ground being played to. They include many new illustrations and they have uncovered unfamiliar relevant texts. There is a good section on how the language of kolf entered into daily discourse, notably in proverbs, and some new early images of ladies at play in Europe. There is a long diversion on women’s golf in general, plus an essay on royalty’s interest in golf worldwide.

Book review in 'Through The Green', magazine of the BGCS, March 2012

Michael Riste, co-founder of the British Columbia Golf Museum, Canada

I am thoroughly enjoying your new book.

December 2011

Wayne Aaron, member of the Golf Collectors Society, USA

December 2011

Dirk Spijker, The Netherlands

Als ik artikelen over colf of kolf lees, is het meestal het zelfde verhaal met weinig nieuws aan de horizon. Niet alleen als lezer krijgen we veel informatie over de vier spelen, maar jullie hebben veel onderwerpen behoorlijk uitgediept, zoals het spelmateriaal en in bijzonderheid: de ballen.

Goed dat jullie aandacht geven hebben aan de ‘onjuistheden’, verhalen die niet kloppen, maar steeds weer terug keren. Als schrijver of onderzoeker denk je soms ‘zo zal het wel geweest kunnen zijn', maar velen hebben met hun mening hiermee de geschiedenis vervalst.

Leuk is ook dat alles op een rijtje gezet is wat betreft de bakermat van golf en de discussie omtrent de herkomst.

Kortom, wij, de liefhebbers van stok- en balspelen, zijn een prachtig boek rijker geworden.

November 2011

Neil JB Laird, owner of the site Scottish Golf History, Great Britain

November 2011

Prof. Dr. Dietrich R. Quanz, Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln, Deutsches Golf Archiv, Germany

Eure Kritik an den falschen Thesen der anderen ist immer sehr vornehm, etwa an H. Gill. ...

An Hand der Regelentwicklung im Fußball und seiner Vorgänger hat man die umstrittene These aufgestellt, dass Spielkultur über die Regeln zunehmend domestiziert wurde – bis hin zu ausdrücklich beim YMCA erfundenen, körperlosen Spielen wie Basketball, wo man ein Foul selber durch Armheben anzeigt, und zu Volleyball, bei dem man nicht ins Spielfeld der anderen darf. Da aber zu wenig Regelmaterial und Regelgeschichte bei Golf und den Vorläufern/Parallelen bekannt ist, wird man hier keinen entsprechenden Ansatz finden.

November 2011

The Netherlands

Hierbij de welgemeende complimenten voor de volledigheid en de zorgvuldige samengestelling. Wat een plezier om te lezen. Een echte aanwinst voor de kolfbibliografie!

November 2011

Encore bravo pour ce beau livre! [...]

October 2011

Alleraardigst vind ik jullie insteek als jullie de spelen colf, kolf, malie en golf onderwerpen aan dezelfde toetsingscriteria (participatie van vrouwen, verschillen tussen de ballen, e.d.). Naar mijn mening een bijzonder onderscheidende insteek die de overeenkomsten én de verschillen tussen deze spelen duidelijk maakt. Ik ben natuurlijk geen echte deskundige, maar volgens mij is deze insteek nooit eerder gekozen. Ook las ik voor het eerst uitvoerig de 'details achter' de maliebaan in Londen. Leuk om te weten!

October 2011

CHOULE The Non-Royal but most Ancient Game of Crosse

The book

| Ordering |

| Reactions & Reviews |

Summary of the chapters of the book

What is jeu de crosse?

Just a Sunday club match

Jeu de crosse is a team game. Two teams of two crosseurs (chouleurs and

déchouleurs) play against each other. The match consists of several parties

(holes in golf). The chouleurs try to reach the target within a certain number

of strokes, decided upon beforehand. The déchouleurs try to prevent that by

hitting that same ball in a different direction, away from the target. The

teams play the ball in turn. The chouleurs hit the ball three times in a row,

after which the déchouleurs hit the ball once. The chouleurs are the winners

when they hit the target within the number of strokes decided upon beforehand.

The déchouleurs are the winners when they succeed in preventing the chouleurs

from achieving their objective. A match is over when one of the teams has won 5

times. A match lasts approximately 4-5 hours.

More than a thousand players play street crosse at carnival in the Belgian town of Chièvres.

Through the ages

Today, crosseurs play their game around the cities of Mons (Bergen) in Belgian Wallonia and Maubeuge in the French region Avesnois. Jeu de crosse en plaine is played on both sides of the Franco-Belgian border. With a few exceptions, crosse au but is played on the French side of the border with the town of Assevent as the centre, while crosse en rue is most popular, with a few exceptions, on the Belgian side of the border, with the cities of Chièvres and Blaton as popular centres.

Just The name

The game at issue did not develop general rules and preserved the old name 'jeu de crosse'. The term choule, internationally used for the crosse game, found its origin in the book 'Golf' from the Badminton Library (1890), in which the game was both wrongly explained and named. As a consequence, in the Anglo-Saxon golf world, the game is still called choule.

The season

Most crosse societies have no playing field of their own. Crosse en plaine is a winter game. In summer, cows and horses occupy the playing fields, or the farmers sow them in. When the pastures and the arable lands are empty again, friendly farmers open their fields to the crosseurs till spring. Matches and tournaments open the season on the 1st of November (All Saints' Day); the grand finals of tournaments often take place on Easter Monday.

The playing field

The choulette (ball)

The Crosse (club)

The players

Considering the many crosse and choulette makers in the past, jeu de crosse must have been very popular. After the Second World War and the closure of the coal mines in the 1960s, the popularity of the game and the number of players reduced dramatically. The youngsters are not interested in the game of their fathers and grandfathers. They prefer playing football, basketball, cycling, etc. There is no glory in being a champion of an almost forgotten game. The field crosse game has always been and still is a men's game. Only in crosse au but, women are well represented.

Clothing

Traditional food

One of the

customs in jeu de crosse is having meals together with traditional food on

special occasions. As crosse

has always been a workman's game, sumptuous haute cuisine dinners were not part

of the crosseur's life. Usually, the players had herring or mussels, the

cheapest food at that time, with a glass of wine or beer. After special festive

days, crosseurs had pork chops or even rabbit. The weekly donations during the

year supplied sufficient money for such a meal.

Tournaments

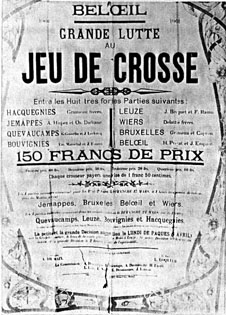

A poster from 1901 announcing an important tournament in Belœil, Belgium.

When the contagious diseases diminished, people stopped going on a pilgrimage to the chapel. The crosseurs, however, continued to go to the chapel of St Anthony, who had since become their patron saint. In his honour, they continued to play their crosse game around the chapel, especially on 17th January, his name day. Because of the fading interest in the game and the building activities around the chapel, this wonderful tradition stopped in 1971.

For several centuries, St Anthony has been the patron saint of all crosseurs.

Ages ago,

people played games like golf and colf in the streets of the towns. In the

centuries, the authorities expelled those games to the neighbouring fields

because of the danger of flying balls causing harm to the public and breaking

windows in churches and houses. Crosseurs yet play in-town, be it only during

carnival. In many villages and cities in the crosse region, players from all

over Wallonia come together. On these festive days, cars are banned from the

streets and windows of the houses and shops are protected with wire mesh or

panels against the bouncing wooden balls. The crosseurs play towards beer

barrels placed in front of the taverns, where they drink to their victory or

defeat of the partie. In some towns, players wear fancy clothes, and when the

games have finished, they often have traditional meals, and they sing

traditional songs.

Several

researchers believe that wars have played an important role in introducing

sports into different regions and countries.

The battle of Hastings in 1066, between William the Conqueror and the

Anglo-Saxon King Edward the Confessor, could have been an event where Flemish

knights introduced jeu de crosse into England, from where it moved to Scotland

to develop into the game of golf.

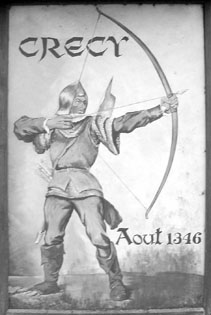

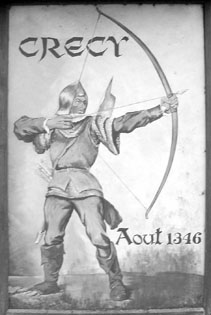

The Hundred Years' War between France and England on French soil culminated in

some major battles, of which we mention Crécy (1346), Poitiers (1356) and Baugé

(1421). English soldiers fought against the French and their Scottish allies.

During the campaigns, the English and Scottish soldiers could have seen French

people playing the crosse game, which they liked so much that they took it with

them to their homeland, where it developed into golf.

In the

Middle Ages and at the beginning of the Renaissance, art had hardly any

other themes than religious ones. Presentations of daily life, like sports,

were exceptional. Later on, to begin in the Low Countries, more profane

depictions appeared, like sports and other pastimes. Various authors have researched these

representations to give the correct name to the games shown. The 'Crécy man' in

Gloucester (England) has caught the attention of many historians. To the ‘ La

Martyre man' in French Brittany and the ‘Airvault man' in French

Poitou-Charente, they paid less attention. The research results were very

diverse; for instance, the Crécy man could play golf, paganica, cambuca or jeu de crosse.

Expressions, proverbs, songs & poems

The ‘Ménétriers' from Chièvres who brought the St Anthony song back to life.

The rules of the game

Rules for the early games of crosse have not been found; they probably did not exist. At that time and age, more than 80% of the population was illiterate. The few basic rules came down from father to son. Such rules were mainly local rules and depended on the terrain where people played the game, such as near little streams and ponds, trees, swamps, meadows, farmland, streets and even churchyards. Therefore, the rules would vary between the different regions or villages. Crosse players in the Middle Ages were mainly ordinary people and farmers who hardly travelled to other regions.The oldest rules we found are from 1928 and written for crossage' au paillet' or 'aux oiseaux' by a Belgian society. It took until 1978 in France before the first 'official' rules for the 'en plaine', 'en rue' and 'omnium' games were edited. In Belgium, the first 'en plaine' rules date from 1980.

After years of research, you conclude that you have raised more questions than you have found answers to questions, for instance, about the differences between crosse and its sister games golf, colf and mail. Questions about the region where the game was and still is played; why there and not elsewhere? Questions about the relationship between crosse and colf played in the neighbouring regions, where the language seems to be a frontier. Questions about the extinction of colf and mail, the tremendous growth of golf and the fight of crosse to survive.

By courtesy of Brian Clough, United Kingdom

The second edition of CHOULE The Non-Royal but most Ancient Game of Crosse

is published in the English language and printed in black and white.

The book contains 200 pages and is illustrated with 200 photographs,

depictions of paintings, drawings and illuminations.

The price of the book is EURO 20 plus p & p.

Payments: via PayPal or an international bank transfer (EURO-accounts only).

Because of

the restricted number of copies printed, the book is not available from the

bookshop, but can be ordered directly via

Reactions on & reviews of the 2008 edition

Pete Georgiady, USA

I have had your book on my

desk since it arrived and I pick it up regularly and read a few more

pages. It is a magnificent work and I salute you for the excellent

research and the high quality manner in which you presented it. It is

very well illustrated (I love most the photo of the boys on p.

77). I would quickly say yours is an important work on the

history of non-golf stick and ball games of western Europe and

one that I will refer to frequently in the future.

July 2011

Literati of the Links, Meeting at St Andrews - Report on the site of the British Golf Collectors Society

Around a dozen of us sat down

in the Byre Theatre to listen to papers presented by David Hamilton, John

Pearson, Philip Knowles and Peter Georgiady in the afternoon of 14th October

2009.

David had recently visited France & Belgium where he witnessed the Ancient

but not so Royal game of Choule being played. He brought with him several

specimens of the balls with which the game is played and an example of the

club.

He described the rules, whereby one team of two "wager" to get the

ball from the teeing off area to a target in a given number of series. A series

comprises three consecutive alternate strokes by the "wagering" team

and then the opposing team being allowed to hit the ball into any other part of

the course. This can be the nearest pond, cow pat, rough grass, or cabbage

patch. The double faced club that is used consists of a flat face to achieve

distance and another with a sharp angle to extract the ball from deep lies.

Whether this game of Chole is an ancestor of golf is debatable. But Geert &

Sara Nijs have produced a wonderful book "Chole The Non-Royal but most

Ancient Game of Crosse" which is a fascinating read.

October 2009

Gordon Taylor, Great Britain

Early in the New Year I received your excellent book on Choule.

I am a collector of golfing memorabilia and have in my collection a

metal crosse club. When I first purchased my club, I did a little

research as to what the game was about and became fascinated with the

rules and how it was played. Your book on which I congratulate you has

now filled in a lot of information which I find intriguing and which

quite obviously has cost you some painstaking research.

February 2009

Cercle Royal d'Histoire & d'Archéologie d'Ath

Janvier 2009

W. Rönnebeck , Germany

A very interesting book and I congratulate you on this scholarly work. It closes a gap, for as you mention, so far most publications on this

topic copied one another. Here, with your book, comes authentic

information.

December 2008

In the opening chapters they give an overview on what is Jeu de Crosse, and its various formats as to whether it is played cross-country or on a smaller scale. It is surprising that this type of game appears to have been limited to quite a small area in northern France and southern Belgium , predominantly in mining areas. Further chapters deal in detail with the different playing layouts that depend on the size and shape of the land available for them to play on. The construction of clubs and balls and the patterns of play are also described.

Geert and Sara express their concern that this game is only played now by a small more elderly part of the society and may be in danger of dying out. They describe the efforts being made to try to maintain its popularity. Like golf the game has a close relationship with food and the different clothing worn by the players. They also explore many other cultural links with the game, including: religion and particularly its nominated patron St. Anthony; carnivals, feasts and battles; other early 'golf' images such as the 'Crécy Man' in the east window of Gloucester Cathedral; and a wide span of literature, songs and poems. I think it would be hard to find two more enthusiastic writers.

Book review in 'Through The Green', magazine of the BGCS , December 2008

Ihr habt mit Fleiß auch nichts ausgelassen, was auf praktische Spielweise und religiös-literarische Bedeutung des Jeu de Crosse einen Lichtschimmer bringen könnte. Das Titelbild und seine Metamorphose in Holzpantinen zieht sich auch thematisch durch: eben kein Spiel der Oberklasse, sondern im wirklichen Sinne ein unkompliziertes Volksspiel. Unkompliziert, weil Ihr es uns im historisch-nationalen Kontext erklärt. An Imagination fehlt es auch nicht und wird wohl zu Diskussionen Anlass geben. Darüber hinaus kommt Ihr am Ende zu vergleichenden Betrachtungen und Fragestellungen aus internationaler Sicht. Es gelingt auch terminologische Verwirrungen aufzulösen und Ordnung zu schaffen zwischen Feld-, Straßen- und Zielorientierung. Ihr räumt mit manchen oberflächlichen-assoziativen Deutungen auf. Gerade bei den 100-jährigen-Kriegsanalysen erinnerte ich mich an Barbara Tuchmanns Buch über das schreckliche 14. Jahrhundert, daß sie an interessanten zeitgenössischen Quellen entwickelt. Ihr habt nicht nur ein historisch anspruchsvolles Arbeitsbuch geschaffen, sondern zeigt und belegt bildlich auch wie lebendig das Spiel in der Gegenwart ist und stellt auf Zukunft ab. Was aus wissenschaftlicher Sicht besonders auffällt: Da wo nicht eindeutig das eine oder andere Stockballspiel gemeint sein kann, gebt Ihr solchen Zweifeln Ausdruck. Das hebt sich besonders von solchen Golfbüchern ab, die für coffe table interessenden und deren Finanzkraft geschrieben und ausgestattet sind.

Second hand books

Deutsch / German

| Deutscher Turnerschaft | Schlagball |

| Diem, Carl | Weltgeschichte des Sports und der Leibeserziehung |

| Heineken, Ph. | Das Golfspiel. Nachdruck von 1898) |

| Heublein, Axel -

Gesammtleitung, Konzept |

100 Jahre Münchener Golf Club E.V. 2010 |

| Labriola, Patrick & Jürgen Schiffer | Das grosse Golf Lexicon |

| Masüger, J.B. | Schweizerbuch der alten Bewegungsspiele |

| Quanz, Dietrich R. -

Konzeption und Redaktion |

100 Jahre Golf in Deutschland In vier Bänden |

|

|